Learn how families can balance safety, dignity, and love when making elder care decisions across generations.

Learn how families can balance safety, dignity, and love when making elder care decisions across generations.

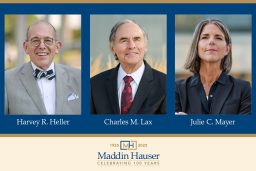

Maddin Hauser is pleased to announce that Chambers USA has again recognized two of our practice groups and three attorneys in its 2025 guide.

In this episode of Forward Focus, Craig Zucker interviews Marc Israel, president of Great Lakes Ventures, about growing a 90-plus-year-old Detroit-based business into a national brand. Learn how leadership, vision, and family values drive lasting success.

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision about the FCC's interpretation of the TPCA and its applicability to online faxes likely means more uncertainty and litigation ahead for marketers.

What legal issues should mortgage professionals consider when moving from one company to another?

Buyers of commercial property who put the contractual cart before the horse by not contacting an attorney until after signing a purchase agreement expose themselves to unnecessary risk and avoidable disaster.